Layered Architecture for Building Readable, Robust, and Extensible Apps

If adding a feature feels like open-heart surgery on your codebase, the problem isn’t bugs, it’s structure. This article shows how better architecture reduces risk, speeds up change, and keeps teams moving.

You know the feeling: your code works but confidence is low so you hesitate to touch it. Adding a feature means performing open-heart surgery on the application, modifying existing business logic rather than extending the system. Over time, the cost of change keeps rising.

Does this feel familiar?

- Changes feel risky because you fear modifying the code might trigger unintended side effects.

- You spend a lot of time scrolling through large files, finding or understanding code

- You have functions that "do everything" and have 10+ parameters.

- Tests are skipped or require spinning up a database, manually preparing records and cleaning up afterwards

- FastAPI routes that construct SQL queries

The application may still be delivering value, but it feels brittle. Structure is unclear, responsibilities are blurred, and small changes feel disproportionately expensive.

If this resonates, this post is for you.

TL;DR

- If adding features feels risky or slow, the problem is often structure, not code quality

- Layered architecture separates responsibilities and keeps business logic independent of frameworks and infrastructure

- Vertical slicing by domain prevents layers from turning into dumping grounds as systems grow

- Application layers orchestrate workflows; domain layers define meaning and constraints

- Clear boundaries reduce cognitive load, improve testability, and make change cheaper over time

Good structure doesn’t add ceremony. It preserves momentum.

The goal of this article

Debating whether a piece of code belongs in one layer or another misses the point. The goal is not perfect categorization but

to architect an application with principles of loosely coupled layers of responsibility that make the system easier to understand, test and evolve.

We aim for application that are:

- Readable: easy to navigate and reason about, with low cognitive load

- Robust: failures are contained, predictable, and understandable

- Extensible: new functionality is added by extension, not by rewriting existing logic. Existing components are loosely coupled, modular and replaceable.

To get there we're going to structure the app into layers, each with a clear responsibility. This separation and the way layers relate to each other allows the system to evolve over time.

Disclaimer:

This is not the best or only way to structure an application and it's not a one-size-fits-all solution.

What follows is a strategy I arrived at by refining it over several years across different projects. I took inspiration from DDD, SOLID principles, onion, hexagonal and layered architecture but combined everything into something that works for the types of systems I typically build.

The Layers

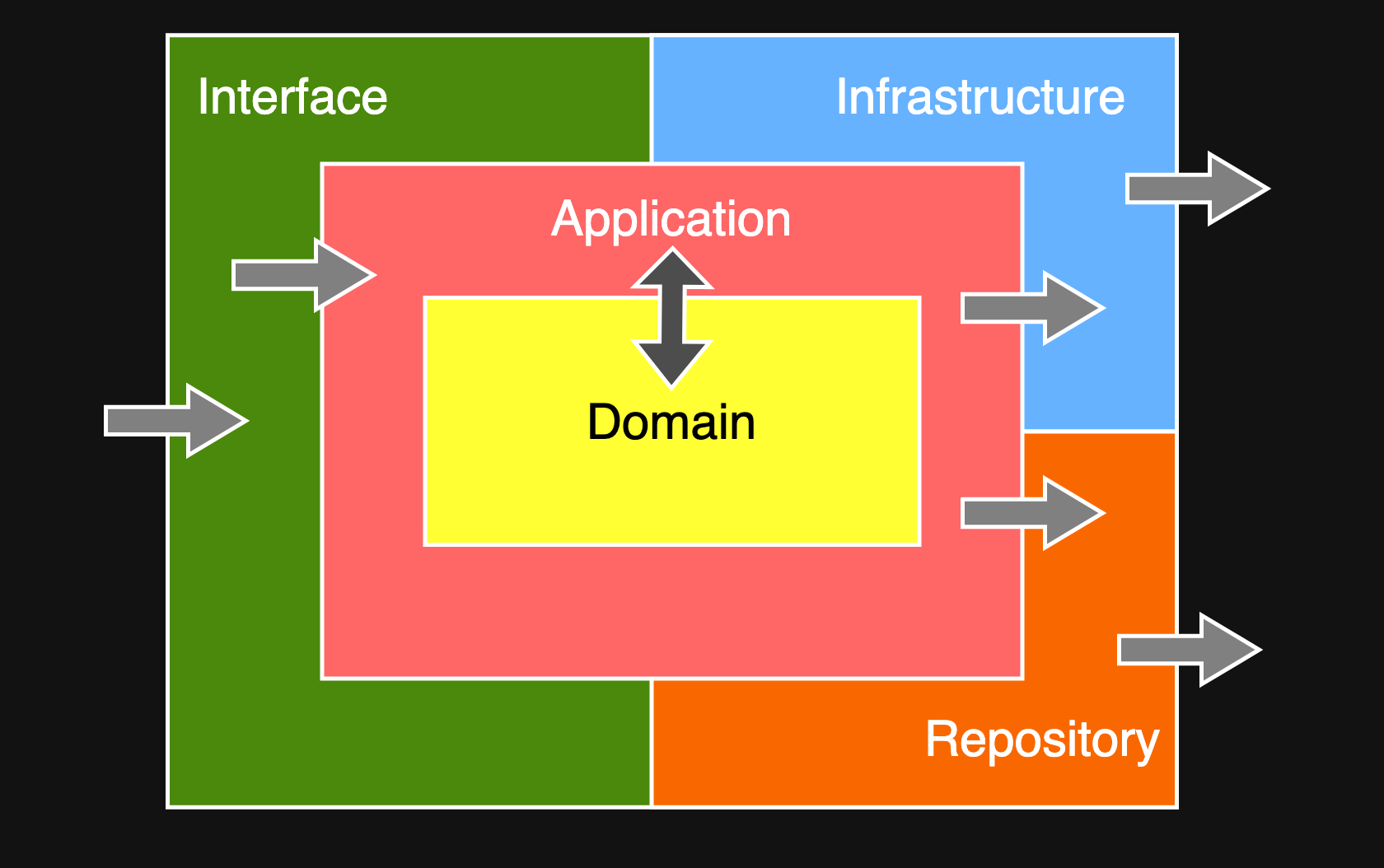

In the image below you'll find an overview of the layered architecture:

Before diving into the responsibilities of each layer, it helps to first understand how they relate to each other.

Layer Relationships (inward flowing dependencies)

The outer layer can be split in two sides:

- Input side

The interface layer, which receives data and acts as the entry point of the app - Output side:

The repository and infrastructure layers, which may communicate with external systems such as API, database and message queues

The interface layer calls the application layer, which is the core of the system, where business logic lives. The application layer, in turn, calls into the repository and infra layers to persist data or communicate externally.

The most important take-away is that dependencies flow inward.

Business logic does not depend on frameworks, database or transport mechanisms. By isolating business logic, we gain clarity and make testing significantly easier.

Domain layer

The domain layer primarily focuses on constraints, not orchestration or side effects. It contains definitions that should reflect business meaning and should be understandable by business people. Think about dataclasses or Pydantic models.

These models define the shape and constraints of the data flowing through the system. They should be strict and fail early when assumptions are violated. Heavy validation ensures high quality data in the core of our system.

A useful side effect is that domain models become a shared language. Non-technical stakeholders may not read the code line-by-line but they can often understand the structure and intent.

Application layer

This is the heart of the system.

The app layer is responsible for orchestrating business logic and workflows. It can get called from the interface layer and coordinates domain models, repositories and infrastructure services to achieve a specific business outcome. In addition it's responsible for handling application-level failures while keeping domain and infrastructure concerns isolated.

A good rule of thumb: If you can unit test this layer without spinning up a database or web server, you are on the right track.

Infrastructure layer

This layer contains anything that supports the app but contains no business logic. Think of this layer as "tools for the app layer"; it only needs to know what to call, not how it is implemented. For example, it should be able to call send_email(...) without knowing anything about SMTP configuration.

By decoupling these concerns you localize complexity and make integrations easier to replace, upgrade or debug.

Examples:

- logging setup

- hashing and crypto utilities

- http clients

- message queue clients

- email senders

Interface layer

The interface layer is how the outside world talks to your system and should act as a gateway for correct data. Think of an API, CLI, queue consumer or something that a CRON job can call.

I keep these layers thin and void of business logic. I aim for just a few responsibilities:

- Receiving input

- Validating and normalizing (transport-level) input (types, format e.g.)

- Calling the application layer

- Formatting the response

Repository layer

The repository layer defines persistence boundaries (e.g. communication with a database). The aim is to decouple your application/business logic from a particular database implementation. This includes ORM models, database schemas, SQL queries, and persistence-related transformations.

The application layer should not be responsible for:

- Which database you use

- How queries are written

- Whether data comes from SQL, a cache or another service

The app layer should be able to just call e.g. get_customer_id(customer_id) and receive a domain object in return. This separation really pays of when you need to switch database, move persistence behind an API, add caching or want to test without a real database.

How to start layering?

It's pretty easy to get started. You don't even have to refactor your whole app right away. It can be as simple as just 5 folders in your src folder at the root of your project:

- src/

- application/

- core.py

- domain/

- customer.py

- infrastructure/

- weather_api_client.py

- interface/

- api/

- (files that contain FastAPI or Flask e.g.)

- cli/

- web/

- (files for a streamlit app e.g.

- repository/

- schemas.py

- customer_repo.pyRemember: the goal is not to pedantically categorize each piece of code in a file and call it a day; the separate files and folders should reflect the fact that your system is layered and decoupled.

Larger apps: Horizontal layering per domain boundary

The example above shows a pretty small application that is layered horizontally only. This works well at first, but larger projects can quickly collapse into "God-modules".

Engineers are smart and will take shortcuts under time pressure. To avoid your layers becoming dumping grounds, you should explicitly add vertical slicing by domain.

Horizontal layering improves structure; vertical slicing by domain improves scalability.

The rules are not about restriction or purity but act as guard rails to preserve architectural intent over time and keep the system understandable as it grows.

Applying horizontal and vertical layers

In practice, this means splitting your application by domain first, and then layering within each domain.

The app in the example below has two domain: subscriptions and users which are both sliced into layers.

src/

application/ <-- this is the composition root (wiring)

main.py

subscriptions/ <-- this is a domain

domain/

subscription.py

cancellation_reason.py

application/

cancel_subscription.py

repository/

subscription_repo.py

infrastructure/

subscription_api_client.py

interface/

api.py

users/ <-- another domain

domain/

application/

repository/

interface/

In the structure above main.py is the composition root which imports and calls functions from the application layer in the subscriptions and users domains and connects them to infrastructure and interfaces. This dependency flows inward, keeping the domains themselves independent.

Core rules

Layering and domain boundaries give our app structure but without some basic rules the architecture collapses quietly. Without rules the codebase slowly drifts back to hidden coupling, circular dependencies and domain logic leaking across boundaries.

To preserve structure over time I use three rules. These rules are intentionally simple. Their value comes from consistent application, not strict enforcement:

Rule 1: Domains do not import each other’s internals.

If subscriptions imports users.domain.User directly you can no longer change users without affecting subscriptions. Because you lose clear ownership, this makes testing this domain in isolation a lot harder.

- Move truly shared concepts into a

shareddomain or - pass data explicitly via interfaces or DTO's (often as IDs rather than objects)

Rule 2: Shared concepts go in a shared domain

This makes coupling explicit and intentional to avoid "shared" things getting duplicated inconsistently or worse: one domain silently becomes the "core" everything depends on.

- keep the domain small and stable

- it should change slowly

- it should contain abstractions and shared types, not workflows

Rule 3: Dependencies flow inward inside each slice

This keeps business logic independent of delivery and infrastructure.

You'll notice when this rule is broken when domain or application code starts depending on FastAPI or a database, test will become slow and brittle and framework upgrades ripple through the codebase.

Keep dependencies flowing inward to ensure that:

- You can swap interfaces and infrastructure

- You can test core logic in isolation

- Your business logic survives change at the edges

Practical example: refactoring a real endpoint

To illustrate the benefits, consider an endpoint that cancels a magazine subscription and returns alternative suggestions.

The initial implementation put everything in a single FastAPI endpoint:

- Raw SQL

- Direct calls to external APIs

- Business logic embedded in the HTTP handler

The code worked, but it was tightly coupled and hard to test. Any test required a web server, a real database, and extensive setup and cleanup.

Refactored design

We refactored the endpoint by separating responsibilities across layers.

- Interface layer

API route that validates input, calls the application function, maps exceptions to HTTP responses. - Application layer

Orchestrates the cancellation workflow, coordinates repositories and external services, and raises use-case level errors. - Repository layer

Centralizes database access, simple functions likeget_user_email(user_id). - Infrastructure layer

Contains API clients for externalSubscriptionAPIandSuggestionAPI, isolated from business logic. - Domain layer

Defines core concepts such asUserandSubscriptionusing strict models.

Result

The endpoint became a thin adapter instead of a God-function. Business logic can now be tested without spinning up an API server or a database. Infrastructure is replaceable and the code-base is more readable.

Change is much cheaper; new features are built by adding new code instead of rewriting existing logic. New engineers ramp up faster due to reduced cognitive load. This makes for a far more robust app that can safely evolve.

Conclusion

Layered design is not about adding ceremony or chasing a textbook ideal. It's about ensuring your system remains understandable and adaptable as it grows.

By separating responsibilities and keeping layers loosely coupled, we reduce the cognitive load of navigating the codebase. This makes failures easier to isolate, and allows new functionality to be added by extension rather than by rewriting existing logic.

These benefits compound over time. Early on, this structure might feel like double work or unnecessary overhead. But as complexity increases the payoff becomes clear: changes become safer, testing becomes cheaper and teams move faster with greater confidence. The system remains stable while interfaces, infrastructure and requirements are able to change around it.

Ultimately, a well-layered application makes change cheaper. And in the long run, that’s what keeps software useful.

I hope this article was as clear as I intended it to be but if this is not the case please let me know what I can do to clarify further. In the meantime, check out my other articles on all kinds of programming-related topics.

Happy coding!

— Mike

P.s: like what I'm doing? Follow me!