Pydantic Performance: 4 tips on how to Validate Large Amounts of Data Efficiently

Pydantic's Rust core enables high-throughput validation, but only when used intentionally. This article examines four common gotchas and explains how aligning model design with the validation engine improves clarity, scalability, and performance.

Many tools in Python are so easy to use that it's also easy to use them the wrong way, like holding a hammer by the head. The same is true for Pydantic, a high-performance data validation library for Python.

In Pydantic v2, the core validation engine is implemented in Rust, making it one of the fastest data validation solutions in the Python ecosystem. However, that performance advantage is only realized if you use Pydantic in a way that actually leverages this highly optimized core.

This article focuses on using Pydantic efficiently, especially when validating large volumes of data. We highlight four common gotchas that can lead to order-of-magnitude performance differences if left unchecked.

1) Prefer Annotated constraints over field validators

A core feature of Pydantic is that data validation is defined declaratively in a model class. When a model is instantiated, Pydantic parses and validates the input data according to the field types and validators defined on that class.

The naïve approach: field validators

We use a @field_validator to validate data, like checking whether an id column is actually an integer or greater than zero. This style is readable and flexible but comes with a performance cost.

class UserFieldValidators(BaseModel):

id: int

email: EmailStr

tags: list[str]

@field_validator("id")

def _validate_id(cls, v: int) -> int:

if not isinstance(v, int):

raise TypeError("id must be an integer")

if v < 1:

raise ValueError("id must be >= 1")

return v

@field_validator("email")

def _validate_email(cls, v: str) -> str:

if not isinstance(v, str):

v = str(v)

if not _email_re.match(v):

raise ValueError("invalid email format")

return v

@field_validator("tags")

def _validate_tags(cls, v: list[str]) -> list[str]:

if not isinstance(v, list):

raise TypeError("tags must be a list")

if not (1 <= len(v) <= 10):

raise ValueError("tags length must be between 1 and 10")

for i, tag in enumerate(v):

if not isinstance(tag, str):

raise TypeError(f"tag[{i}] must be a string")

if tag == "":

raise ValueError(f"tag[{i}] must not be empty")

The reason is that field validators execute in Python, after core type coercion and constraint validation. This prevents them from being optimized or fused into the core validation pipeline.

The optimized approach: Annotated

We can use Annotated from Python's typing library.

class UserAnnotated(BaseModel):

id: Annotated[int, Field(ge=1)]

email: Annotated[str, Field(pattern=RE_EMAIL_PATTERN)]

tags: Annotated[list[str], Field(min_length=1, max_length=10)]This version is shorter, clearer, and shows faster execution at scale.

Why Annotated is faster

Annotated (PEP 593) is a standard Python feature, from the typing library. The constraints placed inside Annotated are compiled into Pydantic's internal scheme and executed inside pydantic-core (Rust).

This means that there are no user-defined Python validation calls required during validation. Also no intermediate Python objects or custom control flow are introduced.

By contrast, @field_validator functions always run in Python, introduce function call overhead and often duplicate checks that could have been handled in core validation.

Annotated itself is not "Rust". The speedup comes from using constrains that pydantic-core understands and can use, not from Annotated existing on its own.Benchmark

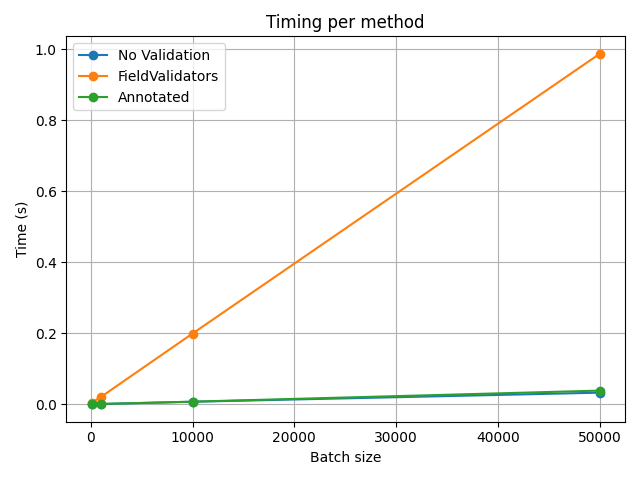

The difference between no validation and Annotated validation is negligible in these benchmarks, while Python validators can become an order-of-magnitude difference.

Benchmark (time in seconds)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Method ┃ n=100 ┃ n=1k ┃ n=10k ┃ n=50k ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━┩

│ FieldValidators│ 0.004 │ 0.020 │ 0.194 │ 0.971 │

│ No Validation │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.007 │ 0.032 │

│ Annotated │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.007 │ 0.036 │

└────────────────┴───────────┴──────────┴───────────┴───────────┘In absolute terms we go from nearly a second of validation time to 36 milliseconds. A performance increase of almost 30x.

Verdict

Use Annotated whenever possible. You get better performance and clearer models. Custom validators are powerful, but you pay for that flexibility in runtime cost so reserve @field_validator for logic that cannot be expressed as constraints.

2). Validate JSON with model_validate_json()

We have data in the form of a JSON-string. What is the most efficient way to validate this data?

The naïve approach

Just parse the JSON and validate the dictionary:

py_dict = json.loads(j)

UserAnnotated.model_validate(py_dict)The optimized approach

Or use a Pydantic function:

UserAnnotated.model_validate_json(j)Why this is faster

model_validate_json()parses JSON and validates it in one pipeline- It uses Pydantic interal and faster JSON parser

- It avoids building large intermediate Python dictionaries and traversing those dictionaries a second time during validation

With json.loads() you pay twice: first when parsing JSON into Python objects, then for validating and coercing those objects.

model_validate_json() reduces memory allocations and redundant traversal.

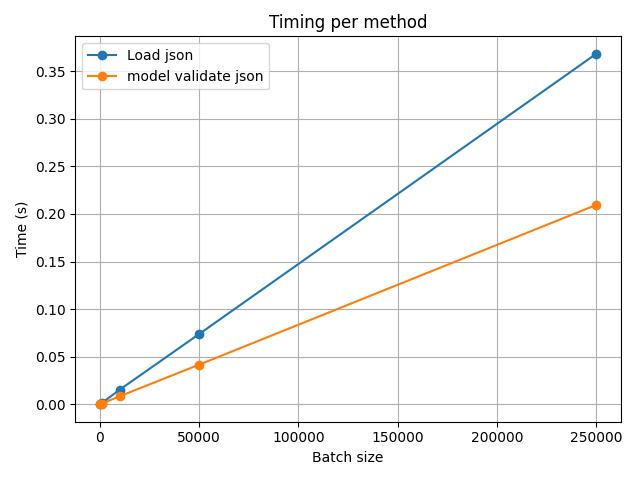

Benchmarked

The Pydantic version is almost twice as fast.

Benchmark (time in seconds)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Method ┃ n=100 ┃ n=1K ┃ n=10K ┃ n=50K ┃ n=250K ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━┩

│ Load json │ 0.000 │ 0.002 │ 0.016 │ 0.074 │ 0.368 │

│ model validate json │ 0.001 │ 0.001 │ 0.009 │ 0.042 │ 0.209 │

└─────────────────────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴────────┘In absolute terms the change saves us 0.1 seconds validating a quarter million objects.

Verdict

If your input is JSON, let Pydantic handle parsing and validation in one step. Performance-wise it isn't absolutely necessary to use model_validate_json() but do so anyway to avoid building intermediate Python objects and condense your code.

3) Use TypeAdapter for bulk validation

We have a User model and now we want to validate a list of Users.

The naïve approach

We can loop through the list and validate each entry or create a wrapper model. Assume batch is a list[dict]:

# 1. Per-item validation

models = [User.model_validate(item) for item in batch]

# 2. Wrapper model

# 2.1 Define a wrapper model:

class UserList(BaseModel):

users: list[User]

# 2.2 Validate with the wrapper model

models = UserList.model_validate({"users": batch}).usersOptimized approach

Type adapters are faster for validating lists of objects.

ta_annotated = TypeAdapter(list[UserAnnotated])

models = ta_annotated.validate_python(batch)Why this is faster

Leave the heavy lifting to Rust. Using a TypeAdapter doesn't required an extra Wrapper to be constructed and validation runs using a single compiled schema. There are fewer Python-to-Rust-and-back boundry crossings and there is a lower object allocation overhead.

Wrapper models are slower because they do more than validate the list:

- Constructs an extra model instance

- Tracks field sets and internal state

- Handles configuration, defaults, extras

That extra layer is small per call, but becomes measurable at scale.

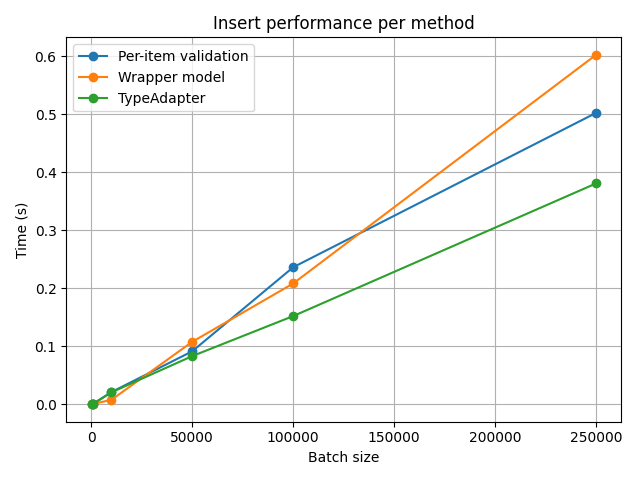

Benchmarked

When using large sets we see that the type-adapter is significantly faster, especially compared to the wrapper model.

Benchmark (time in seconds)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Method ┃ n=100 ┃ n=1K ┃ n=10K ┃ n=50K ┃ n=100K ┃ n=250K ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━┩

│ Per-item │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.021 │ 0.091 │ 0.236 │ 0.502 │

│ Wrapper model│ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.008 │ 0.108 │ 0.208 │ 0.602 │

│ TypeAdapter │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.021 │ 0.083 │ 0.152 │ 0.381 │

└──────────────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴────────┴────────┘In absolute terms, however, the speedup saves us around 120 to 220 milliseconds for 250k objects.

Verdict

When you just want to validate a type, not define a domain object, TypeAdapter is the fastest and cleanest option. Although it is not absolutely required for time saved, it skips unnecessary model instantiation and avoids Python-side validation loops, making your code cleaner and more readable.

4) Avoid from_attributes unless you need it

With from_attributes you configure your model class. When you set it to True you tell Pydantic to read values from object attributes instead of dictionary keys. This matters when your input is anything but a dictionary, like a SQLAlchemy ORM instance, dataclass or any plain Python object with attributes.

By default from_attributes is False. Sometimes developers set this attribute to True to keep the model flexible:

class Product(BaseModel):

id: int

name: str

model_config = ConfigDict(from_attributes=True)

If you just pass dictionaries to your model, however, it's best to avoid from_attributes because it requires Python to do a lot more work. The resulting overhead provides no benefit when the input is already in plain mapping.

Why from_attributes=True is slower

This method uses getattr() instead of dictionary lookup, which is slower. Also it can trigger functionalities on the object we're reading from like descriptors, properties, or ORM lazy loading.

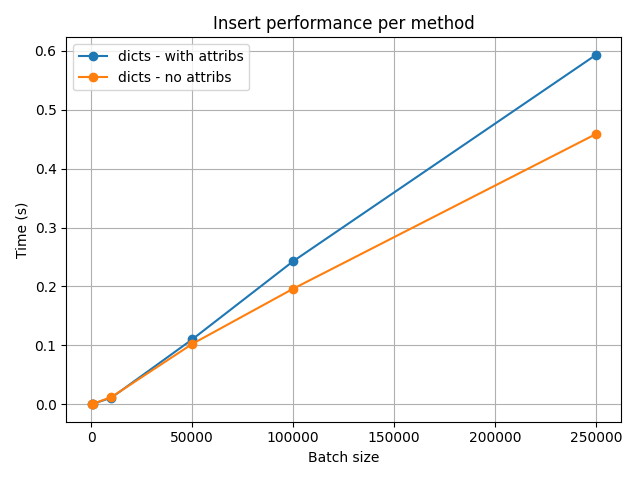

Benchmark

As batch sizes get larger, using attributes gets more and more expensive.

Benchmark (time in seconds)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Method ┃ n=100 ┃ n=1K ┃ n=10K ┃ n=50K ┃ n=100K ┃ n=250K ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━┩

│ with attribs │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.011 │ 0.110 │ 0.243 │ 0.593 │

│ no attribs │ 0.000 │ 0.001 │ 0.012 │ 0.103 │ 0.196 │ 0.459 │

└──────────────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴────────┴────────┘In absolute terms a little under 0.1 seconds is saved on validating 250k objects.

Verdict

Only use from_attributes when your input is not a dict. It exists to support attribute-based objects (ORMs, dataclasses, domain objects). In those cases, it can be faster than first dumping the object to a dict and then validating it. For plain mappings, it adds overhead with no benefit.

Conclusion

The point of these optimizations is not to shave off a few milliseconds for their own sake. In absolute terms, even a 100 ms difference is rarely the bottleneck in a real system.

The real value lies in writing clearer code and using your tools right.

Using the tips specified in this article leads to clearer models, more explicit intent, and a better alignment with how Pydantic is designed to work. These patterns move validation logic out of ad-hoc Python code and into declarative schemas that are easier to read, reason about, and maintain.

The performance improvements are a side effect of doing things the right way. When validation rules are expressed declaratively, Pydantic can apply them consistently, optimize them internally, and scale them naturally as your data grows.

In short:

Don’t adopt these patterns just because they’re faster. Adopt them because they make your code simpler, more explicit, and better suited to the tools you’re using.

The speedup is just a nice bonus.

I hope this article was as clear as I intended it to be but if this is not the case please let me know what I can do to clarify further. In the meantime, check out my other articles on all kinds of programming-related topics.

Happy coding!

— Mike

P.s: like what I'm doing? Follow me!