Virtual environments for absolute beginners — what is it and how to create one (+ examples)

A deep dive into Python virtual environments, pip and avoiding entangled dependencies

If you work on a lot of different projects then you’ll recognize the dependency-hell of multiple projects requiring multiple versions, of multiple packages. You can’t just install all packages globally, how do you keep track? Also what happens when projectA needs PackageX_version1 and ProjectB needs PackageX_version2? How do you stay sane when everything is one big jumbled spaghetti-like mess of interdependency?

In this article I’ll try to convince that using a venv (virtual environment) is the way to keep dependencies separate from other projects. We’ll start with defining what a venv is, what it does and why you need it. Then we’ll create one and see all of its benefits. At the end we’ll have some basic rules to keep dependencies in our projects as clean as possible.

1. What is a venv and why would I need one?

What happens when one of your projects need a package with a different version than an other project? What happens when you update a package for one project: will it ruin your code in another project that depends on that package? How do you share your code with others?

To get an idea of what a venv is we’re going to cut it up into two parts: virtual and environment.

Environment

An environment you’re already familiar with. When you install Python3.10 for example then you don’t just install the Python engine, also pip gets installed. When you use pip to install a package it ends up in the Scripts folder in the directory where you installed Python. This is your environment: Python 3.10 with all of the installed packages.

If you run your program like python main.py this happens:

- your system looks up where you have python installed via the system PATH variable so it translates your command to something like

C:\Program Files\Python39\python.exe main.py. - Next your script main.py gets passed to the Python engine. If you for example

import requestssomewhere in your script it’s going to look up this package in the directory where python is installed, in theLibfolder (in my caseC:\Program Files\Python39\Lib). - If you have the package installed python can find it in this folder and import the code so you can use it, else it returns an error saying the package you are trying to import is not installed

This global installation of Python is your only environment if you do not make use of virtual environments. You can see that keeping all of your projects’ dependencies bundled up in one big box can be dangerous. Time to split this up into virtual environments.

Virtual

I like to think of a venv as creating a whole new, somewhat lighter environment specifically for this project. We’ll see in the coming parts that when you create a venv for your project you actually install Python, pip and the dependencies-folder anew for this specific project. This code doesn’t reside in your default Python path (e.g. C:\Program Files\Python39) but can be installed anywhere, for example in your project folder (e.g. C:\myProject\weatherApp\venv).

Sharing and building the environment

Once you have a virtual environment, you can tell it to create a list for you of all of the packages it contains. Then, when someone else wants to use your code, they can create a venv of their own and use this list to install all the packages, with the right versions all at once. This makes it very easy to share your code with others (via git, mail or usb-stick).

2. Creating a virtual environment

Let’s create our virtual environment! In the steps below we’ll make sure that a virtual environment can be created. For this part it is recommended to read the article if you are inexperienced or unfamiliar with using a terminal. We’ll use a Python package called virtualenv to create our venvs.

2.1 Have Python installed

- Check your system architecture; it’s either 32 or 64 bits.

- Download and install Python from the python website. Make sure to match your system (32 or 64 bits.

- Python is correctly installed if you see the version you’ve installed after executing

python --versionin a terminal.

2.2 Install virtualenv

Virtualenv is a Python package that allows us to create the venvs. We’ll install it globally on our machine.

- Install virtualenv package using pip: We simply install it by calling

pip install virtualenv - Virtualenv is correctly install if you can execute

python -m virtualenv -h.

This command tells python to load one of it’s (-m) modules, that is the virtualenv module. The -h flag asks virtualenv to show the “help” options. It it shows you some tips then you know it’s correctly installed.

2.3 Creating our first virtual environment

Now that we have the software to create virtual environments we can make one.

- Navigate to the folder where you want to create your project. We’ll call this the root folder. In my case this is

cd c:/applications/newpythonproject. - Tell Python to use venv to create a new virtual environment

python -m venv c:/applications/newpythonproject/venv`

This will create a new directory in your root folder called venv containing a fresh version of python and pip. We will install our packages in here.

3. Using our virtual environment

Lets start using our virtual environment. In this part we’ll activate it, install some packages and deactivate it again.

3.1 Activating our virtual environment

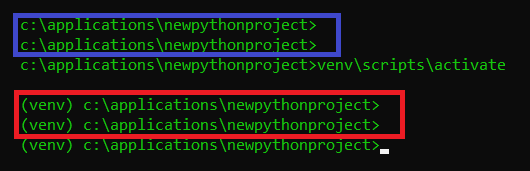

When we run pip install requests now it will still install them globally, which is not what we want. In order to install packages inside our venv we have to activate our venv in order to install them there. In your root folder we execute this command: venv\scripts\activate. (notice the slashes are \, the other ones (/) won’t work.

If your environment is activated you’ll see (venv) before your path in your terminal like in the image above. Every package that your will pip install now will be installed in your virtual env.

3.2 Using our virtual environment

Calling e.g. pip install requestsnow will install it in your venv. You can see this by calling pip list` in your activated environment; you’ll see requests there. If you, on the other hand, call pip list in another terminal (where no venv is activated) you’ll see a different list of installed packages.

3.3 Deactivating our virtual environment

You can deactivate your venv by simply executing deactivate in your terminal.

4. Exporting and building the venv

You’ve created an app what works with some dependencies. Let’s say you’ve installed requests and pandas to request data from an API, do some cleaning in pandas and then saving it to a file. Now you want others to use your program but here’s the problem: they need to install exactly the same dependencies with the correct versions and all. Lets give them a list.

4.1 List your dependencies in requirements.txt

Image you have a list of packages that your program depends on. Pip could read this list and install all the packages.

This is exactly what the requirements.txt does. It freezes the content of pip list in a text file using the following command pip freeze > requirements.txt. Dead simple! The only thing to note is that the command above creates the requirements.txt file in the folder you are currently in, e.g. your root folder. You can also freeze the file somewhere else or with a different name pip freeze > c:/some/other/path/mylist.txt but this is not recommended.

4.2 Loading your dependencies

If you have a requirements.txt you can simply call pip install -r requirements.txt for pip to install all the packages listed. The -r flag stands for read so pip installs all the packages it reads in the file your specifying.

Note again that it searches for requirements.txt in the folder you’re currently in. You can also load it from another location like pip install -r c:/some/other/location/requirements.txt.

4.3 Ignore virtual environments in git

If you want to add you project to a version control system like Github it’s not recommended to include your entire virtual environment. This takes up a lot of space and time to upload and download.

It’s recommended to tell git to ignore your folder containing your virtual environment. In order to do this you can simply create a file in your root folder called .gitignore (notice that gitignore is the extension, this file has no name), and give it the following content venv/. This tells git to ignore your venv folder. If the folder you’ve saved your venv in is called something else, you obviously have to write down the correct folder name here.

4.4 Installing packages from git projects with excluded venv

Now what happens when Bob pulls your code from Github and wants to use your program? If you were smart you froze your packages to a requirements.txt. Bob can simply pip install -r requirements.txt and start using your program!

4.5 Virtual environments, requirements.txt and docker

Docker needs a list of instructions to build the container and requirements.txt is perfect for this. The Dockerfile can look like this:FROM python:3.9-slim-buster# 1. Copy application code to a folder in container

COPY . /usr/src/downloadService# 2. Cd to the folder

WORKDIR /usr/src/downloadService# 3. Tell pip to install all required packages

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt# 4. Execute app

EXPOSE 5000

WORKDIR /usr/src/downloadService/src

CMD ["python", "-i", "app.py"]

Don’t worry if you are inexperienced with Docker, just know that we can automatically transport all of our source code inside a container, install all packages (# 3) and then start up our app.

5. Best practices: prevent dependency hell

Dependency hell is when all of our projects are entangled through their dependencies. This is hard enough to avoid working on your own but especially when you’re working in a team. This part tries to lay down some ground rules of how to work with Python project.

- Every python project gets it’s own virtual environment

- Freeze dependency hell with

pip freeze! Update your requirements.txt on every install or uninstall - Include a file called

pythonversion.txtin your root in which your python version is recorded (python --version).

- Not always required: build the app in a Docker container so you keep track of the OS as well

Following these rules there should be no question about the type and version of the OS, python and all of its dependencies.

Conclusion

I hope I could clarify virtual environments and the way Python installs dependencies and how to keep dependencies to become tangled across projects.

If you have suggestions/clarifications please comment so I can improve this article. In the meantime, check out my other articles on all kinds of programming-related topics like these:

- Why Python is slow and how to speed it up

- Advanced multi-tasking in Python: applying and benchmarking threadpools and processpools

- Write you own C extension to speed up Python x100

- Getting started with Cython: how to perform >1.7 billion calculations per second in Python

- Create a fast auto-documented, maintainable and easy-to-use Python API in 5 lines of code with FastAPI

- Create and publish your own Python package

- Create Your Custom, private Python Package That You Can PIP Install From Your Git Repository

- Virtual environments for absolute beginners — what is it and how to create one (+ examples)

- Dramatically improve your database insert speed with a simple upgrade

Happy coding!

— Mike

P.S: like what I’m doing? Follow me!